The Value of Credentials: Why They Matter In and Beyond the World of Sports

In today’s fast-moving, hyperconnected world, it’s tempting to discount the value of credentials. For some, diplomas and certificates may be seen as gatekeeping or outdated. But whether on the field, in the clinic or behind the scenes, credentials serve a vital purpose: They are society’s way of ensuring a minimum standard of competence and ethics. In sports and beyond, they matter more than ever.

What Are Credentials, Really?

At their core, credentials are tools of accountability. They are not a measure of genius or talent, nor are they a guarantee of greatness. Rather, they signify that someone has met a baseline set of knowledge, skills and ethical standards in a particular domain. A minimal level of competency.

A certified athletic trainer, a licensed physical therapist, a sport psychologist credentialed by a recognized body — each of these professionals has passed through rigorous training and testing. That process exists to protect the people they serve.

In sports, credentials are particularly vital because of the stakes involved. A coach without proper training can push an athlete past safe limits, risking injury or burnout. A strength trainer without a solid foundation in biomechanics might unknowingly encourage dangerous form. A mental skills consultant without psychological training could overstep into areas better handled by a licensed clinician.

And beneath all of this lies an ethical contract. Credentialed professionals are not just tested for what they know — they are also required to operate within clear boundaries. They must adhere to codes of conduct, respect client confidentiality and recognize the limits of their expertise. Ethics, like competence, must be taught, reinforced and reviewed. Credentials help ensure that happens.

Sports as a Microcosm

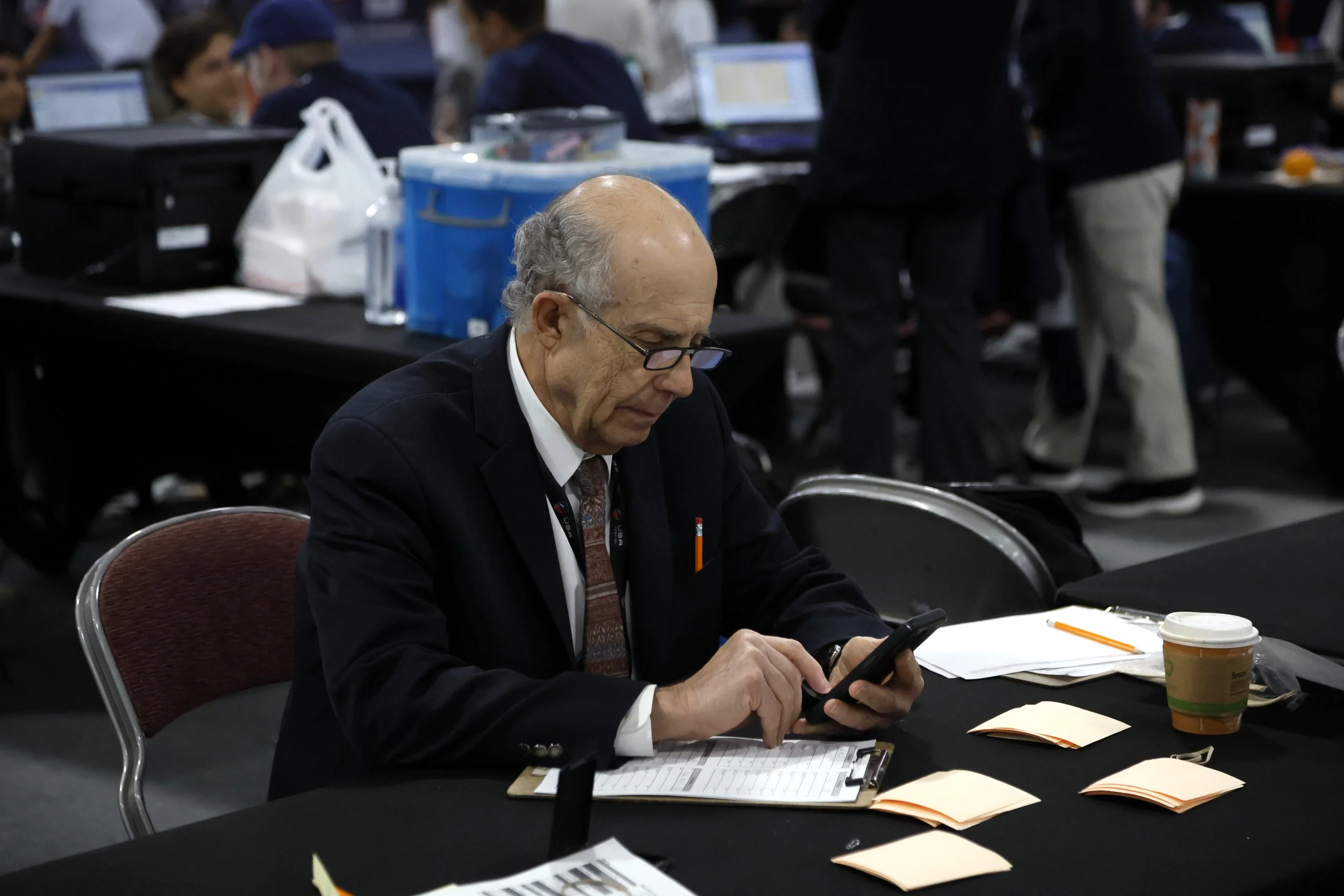

Sport offers a particularly clear example of why credentials matter. Consider the layers of certification involved in organizing a single youth fencing competition: referees are trained and tested, armorers must know the rules of equipment safety and coaches are expected to maintain safe, ethical practice environments. These aren’t just bureaucratic checkboxes — they are safeguards.

We accept without question that referees must pass certification exams. Why? Because we want them to make consistent, fair calls based on a known rule set. That same logic applies to strength and conditioning coaches, athletic directors and mental performance professionals. The role may change, but the principle remains: training matters. Testing matters. Standards — and ethics — matter.

This is not to say that credentials alone are enough. They are a starting point, not a destination. But without them, we are left to guess someone’s qualifications and trust charisma or confidence rather than competence and integrity.

The Illusion of Experience Without Training

It’s common to hear someone say, “I don’t have the degree, but I’ve been doing this for 20 years.” Experience can be valuable — even essential — but only when paired with structured learning. Someone who has coached for decades but has never studied anatomy, learning theory or ethical practice may be limited in ways they can’t see. Worse, they may be passing-on poor habits or misinformation.

Credentials are not just about checking technical knowledge, they also shape how professionals think about boundaries. For example, a mental performance coach who hasn’t been trained in ethical guidelines may not understand when they’ve crossed the line into clinical territory. That’s not just a mistake — it’s a violation that can do real harm.

In contrast, credentialing bodies usually require not just a one-time exam but ongoing education in both content and ethics. A licensed practitioner is expected to know what to do — and to know when they must refer out. That distinction is essential, especially when working with young athletes, vulnerable populations or high-pressure environments.

Outside the Arena: The Broader Application

Credentials are not only vital in sports — they are essential across all disciplines where people place their trust in others. We wouldn’t let someone perform surgery without a medical license. We don’t want a pilot flying a commercial jet without certification. These are obvious examples because the dangers are immediate and visible.

But the same principle applies more quietly in other fields. A financial advisor managing retirement funds. A therapist guiding someone through trauma. A nutritionist creating a diet plan for a diabetic client. These professionals are entrusted with people’s health, finances and futures. Credentials help verify that they not only know what they’re doing, but that they’re bound by ethical commitments to do it responsibly.

The consequences of working with someone unqualified are not always dramatic, but they can be devastating. An unlicensed therapist can miss signs of a mental health crisis. An unqualified strength coach can create an injury that sidelines an athlete for life. A self-declared nutrition guru can do more harm than good. Credentials don’t eliminate risk, but they reduce it in measurable, meaningful ways.

The Double Standard of Celebrity

In this age of social media, the lines between expertise and entertainment have blurred. A charismatic figure with no formal training can amass a large following and influence decisions in health, fitness and performance. They may have good instincts or compelling anecdotes — but that is not the same as competence backed by training, mentorship and ethical accountability.

Athletes, in particular, are often assumed to be authorities in coaching or sport psychology simply because they’ve competed at a high level. But playing a sport and teaching it are very different skills. Being a successful athlete doesn’t automatically confer the ability to support others through injury, burnout or performance anxiety.

Credentialing introduces a layer of humility and restraint. It demands reflection, critical feedback,= and the maturity to know when to say, “That’s beyond my scope.” That humility is not a weakness — it’s a cornerstone of ethical practice.

If you are really good at brushing your teeth and have never had a cavity, that still doesn’t qualify you to be someone’s dentist!

Making Credentials More Accessible

To be clear, the solution is not blind allegiance to titles or institutions. The credentialing system itself must remain open to scrutiny. It must evolve to reflect the needs of diverse communities. It must avoid being so expensive or exclusive that capable people are shut out. We need more accessible, ethical pathways to training, not fewer.

But whatever the system looks like, the core idea remains: people deserve to know that the on which professionals they rely have passed a meaningful threshold of preparation, competence and ethical training. We all benefit when there are clear standards, when those standards are met and maintained.

When you are considering working with someone in a professional context, part of the conversation should be to ask what their training is and which associated credentials they have earned.

Conclusion: Respect the Threshold

In both sports and life, credentials matter not because they prove someone is the best, but because they show that someone has done the work to meet a defined standard of knowledge, safety and ethical responsibility. That’s not elitism — it’s protection.

When we honor credentials, we don’t shut people out; we protect those who come in. We elevate the level of care, reduce harm and foster a culture of continual learning and ethical behavior. In a world full of self-proclaimed experts, credentials still speak volumes. And we’d be wise to keep listening.

Photos: Serge Timacheff/USA Fencing